Shalom Radio UK – http://www.hotrodronisblog.com

Listen Below>

Due to the great significance of the artistic work of Reuven Rubin in the development of the visual arts and painting in particular in the Land of Israel, it is my intention to continue to look at his work, that he contributed..

Part 3B: Behold the Man:…and the Zionist Messiah*

*[AMATAI MENDELSOHN, BEHOLD THE MAN: JESUS IN ISRAELI ART, MAGNES PRESS, JERUSALEM, 2017, ISBN 978 965 278 465 0].

Rubin’s engagement with the luminous figure of Jesus in three of his paintings and in particular, will be considered: The Madonna of the Vagabonds; Self-Portrait with a Flower; and The Prophet in the Desert.

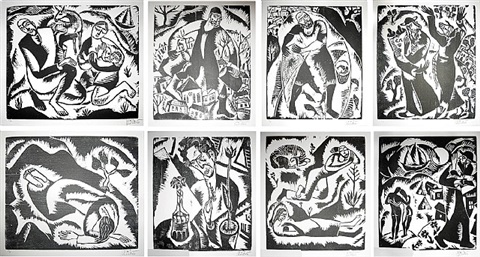

“The God-Seekers” – A woodcut of Jesus with stigmata in his hands

The Prophet in the Desert

Rubin’s spiritual quest was tied up with his interest in the Jewish Scriptural heritage of his people. From a series of woodcut prints that Rubin produced that he entitled,“The God-Seekers,” he interprets the theme that Jesus is a symbol of the regenerated Jew who is destined to take his place and therefore heals the suffering of the Diaspora (p 105). This picture of Jesus (The Prophet in the Desert) bearing stigmata in the outstretched palms of his hands in a gesture of blessing that gave expression to that sentiment.

First Fruits

Prophet

Elijah the Prophet

There is considerable similarity between Rubin’s two painting Jesus and the Last Apostle and The Encounter.

Jesus and the Last Apostle is a large canvas (1 – 1.10 meters) that he painted shortly before his immigration to the Land of Israel (British Mandated Palestine). On inspection the similarity between the between the two pantings is apparent (p 106).

In 1922 Rubin wrote to his friend Bernard Weinberg:

“[I am working] in agony with my very lifeblood, my own and no one else’s,” …”In this last work, I have put all my anguish of my soul, with no understanding from any side and without a ray of light. The nails in the hand and feet of Jesus are burning me, and no one can grasp my suffering” (p 106, Behold).

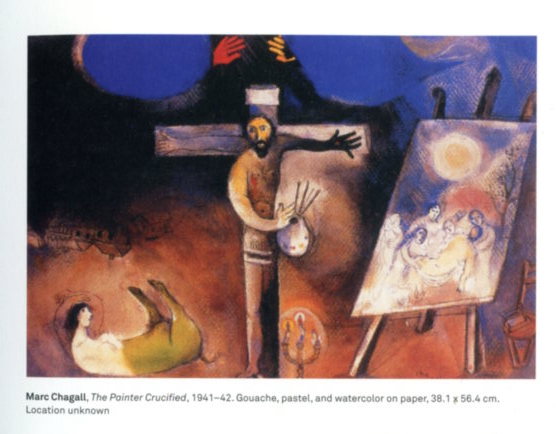

We recall the words and painting that Marc Chagall did:

These are but a few examples of the catalogue of paintings on the theme of Crucifixion that Chagall painted in which he identifies himself with Jesus’ suffering:

“I awake in pain / Of a new day with hopes / Not yet painted / Not yet daubed with paint / I run upstairs to my dry brushes / And I am crucified with Christ / With nails pounded in the easel” – A poem by Chagall and illustrated with his profound painting The Painter Crucified (1941-42); (p 56, Behold the Man).

The Painter Crucified – Marc Chagall

Chagall expressed similar anguish to what Rubin had experienced, some twenty years earlier. Like many creative people, these two Jewish artists gave expression to their sense of anguish, foreboding and even its manifestation in personal physical pain. That deep emotional turmoil is often induced by the suffering that they witness around them. Rubin’s sense of pain is related to the plight of his fellow Jews in Eastern Europe and Chagall in 1942 must have had some knowledge of the huge catastrophe that was engulfing European Jewry during WWII.

The Meaning of Jesus and the Last Apostle

What is the hidden meaning behind Rubin’s painting of Jesus and the Last Apostle?

In this painting, Rubin has not depicted a known scene from the life of Jesus such as his Temptation in the Desert (Matthew 4:1-11), but this is a piece of fiction bearing a powerful message that needs to be examined.

Like other artists and intellectuals of the late 19th and early 20th century, a number of Jewish thinkers began to focus upon the person of Jesus as a Jew. This should not come as a surprise, for according to his human nature Jesus is Jewish. However, if we consider that for two millennia the persecution and suffering heaped upon the hapless Jew in the name of Christ, then it is a surprise and all the more amazing that such a change was taking place despite the bad history of Jews and Jesus.

Bob Dylan’s song, The Times They Are A Changing, adequately gives expression to this change that was happening. Jesus became a symbol of Jewish suffering. We have explored this on numerous occasion in previous Shalom Radio UK, programmes. This Jewish action was a response to hostile attitudes adopted by the Church though engaged in worshipping Jesus, persecuted and showed hatred toward Jews (p 106, Behold).

From the Encounter to the painting of Jesus and the Last Apostle, it appears that Jesus underwent a metamorphosis. For in the Encounter, Jesus sits upright, head held high, displaying his wounds for all to see, with face showing pride and pain.

However, in Jesus and the Last Apostle, the situation to that of Jesus and the Wandering Jew are reversed: Jesus is seated on the left, where the Jew previously sat, his head is bowed with his face completely hidden.

What is the message that Rubin wants to communicate to his viewers?

The key to our understanding is held by the second figure of the Last Apostle! Who is he? For just as Jesus had communicated with his listeners in parables, so Rubin too had a deeper meaning to the imagery that he painted in this compositions.

Gala Galaction

In his letter to Bernard Weinberg, Rubin named a well-known individual called Gala Galaction, a Romanian Orthodox priest as the person upon whom the figure of the Last Apostle is based. Galaction sincere love of the Jewish people of Romania, and he helped mediate between Christians and Jews in a very hostile environment that was anti-Semitic and dangerous for Jews. In addition, this philo-Semitic priest encouraged Zionism and he saw that Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel would be a solution to their plight in Europe.

Because of Galaction’s love of Jewish people, Rubin placed this figure of him as the Last Apostle at the side of Jesus, with Jesus showing his wounds to the Last Apostle. “Jesus seems to be expressing his grief [or] perhaps remorse, at the suffering endured by the Jewish people on his account” (p 106, Behold).

By his depicting Galaction as the Last Apostle, Rubin may have intended to convey a historic reconciliation and a reversal of roles. “Jesus has been transformed: no longer the long-suffering victim for which the Jews are blamed. He hangs his head and asks to be forgiven for the persecution of the Jews [that took place in his name]. The conciliatory figure of Galaction portrays a new kind of apostle, the Last Apostle, who will inspire mutual understanding between the two religions” (p 106, Behold).

Alas, this message of reconciling love expressed by this philo-Semite, Galaction proved to be among an isolated few voices in a Europe that were to carry out its greatest outrage against the Jewish people ever witnessed. With the rise of National Socialism (Nazism) in Germany that began its rise to power in 1933, resulting in the mass murder of 6,000,000 Jews during WWII.

On July 18th, 1925 Adolf Hitler wrote his pernicious book of hate, Mein Kampf (My Struggle) in which he formulated his ideas that resulted in Nazi Germany carrying out the Final Solution resulting in the extermination of two-thirds of the Jews of Europe. Hitler describes his pathological hatred and loathing of the Jews in his book.

Romania, despite the wonderful work of Galaction, also became a killing field of its Jews under the direction of the occupying Nazi’s. A third of its Jewish population perished under Nazi persecution.

As we have seen other Jewish artists such as Anotokolsky, and Marc Chagall shared a similar desire to Rubin, using Jesus’ image in their work as a bridge between Christians and Jews, as was Gottlieb’s intention. Additionally to the message of religious reconciliation, Jesus and the Last Apostle, Rubin to his friend Weinberg expressed his personal identification of his own anguish with that of Jesus the man. This was particularly the case in his painting The Temptation in the Desert, where this Jesus seeks to heal the suffering the Jewish people and he also embodies the artist’s own pain (p 106 & 109, Behold).

In 1922 Rubin exhibited a number of his painting in New York, USA. This included the picture The Suffering of Christ and a sculpture and sketch as Christ Homesick. The record of these “lost and undocumented works offer additional evidence of Rubin’s great interest in the figure of Jesus, and perhaps (in the case of Christ Homesick) in linking him to Zionism” (p 109, Behold).  The Meal of the Poor painted by Rubin in Bucharest and on display at the New York exhibition in 1922, has strong Christian overtones: “Seven despondent, lowly people sit at the foreshortened oval table. At the head of the table is an elderly Rabbi-like figure, (dressed in a coat resembling a kapote worn by traditional Eastern European Jews) breaks the bread. Everyone present is enveloped in a halo-like aura this especially visible around the rabbi and the man seated at the right. On the table are foods are eaten by the poor, slices of watermelon, bread and a solitary fish on a plate – and a glass carafe holding a white lily, the attribute of the Virgin Mary found in many depictions of the Annunciation. Rubin’s works from this period contain the flower motif as a symbol of rebirth, and a white lily features prominently in his well-known work soon after his arrival in Ertez Israel” (p 109)

The Meal of the Poor painted by Rubin in Bucharest and on display at the New York exhibition in 1922, has strong Christian overtones: “Seven despondent, lowly people sit at the foreshortened oval table. At the head of the table is an elderly Rabbi-like figure, (dressed in a coat resembling a kapote worn by traditional Eastern European Jews) breaks the bread. Everyone present is enveloped in a halo-like aura this especially visible around the rabbi and the man seated at the right. On the table are foods are eaten by the poor, slices of watermelon, bread and a solitary fish on a plate – and a glass carafe holding a white lily, the attribute of the Virgin Mary found in many depictions of the Annunciation. Rubin’s works from this period contain the flower motif as a symbol of rebirth, and a white lily features prominently in his well-known work soon after his arrival in Ertez Israel” (p 109)

.

Mariotto di Nardo’s Last Supper

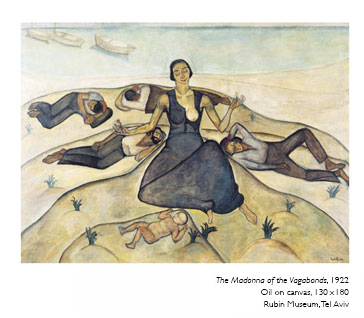

The Madonna and the Vagabonds

The Madonna and the Vagabonds exhibited at the exhibition of Rubin’s work in Bucharest. Like the Encounter painting, with New Testament referencing Jesus is shown as an infant. This use of an infant Jesus symbolises “a pioneer reborn in the Land of Israel” (p 111, Behold).

A number of significant changes should be noted, namely Rubin’s palette is brighter and his new Eretz Israel style witnesses a change from a suffering Jesus to a newborn baby. This change was brought about by his new optimism linked to his immigration to the Land of Israel (p 111, Behold).

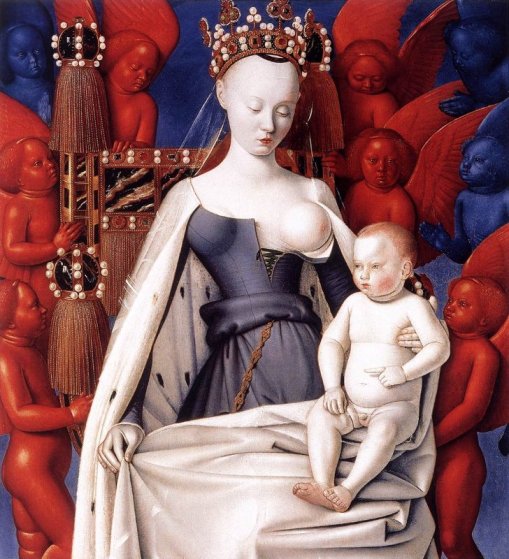

The Nursing Madonna was a popular theme with European artist from the Middle-Ages, with Rubin’s conflation (to fuse into one entity; merge) of this image taken from Christian iconography. The example of the Madonna and Adoring Child first appeared in the 13th century. Sometimes Mary is alone shown worshipping the infant, while other times Joseph is also depicted alongside her.

Rubin may well have been exposed to some of these paintings in his native Romanic or some of the neighbouring countries such as Moldova, where painted images of the Madonna and Adoring Child. These paintings were rendered in a Neo-Byzantine style, like this painting by Jean Fourquet’s Madonna Surrounded by Cherubim and Seraphim (1452).

Jean Fourquet’s Madonna Surrounded by Cherubim and Seraphim (1452).

The Meaning of the Madonna and the Vagabonds

Rubin’s interpretation of the Madonna and the Vagabonds may well represent four apostles in this very unusual representation, with the four figures that surround the Madonna together with the infant Jesus all lying on the ground.

What was behind his thinking in doing this portrayal like that?

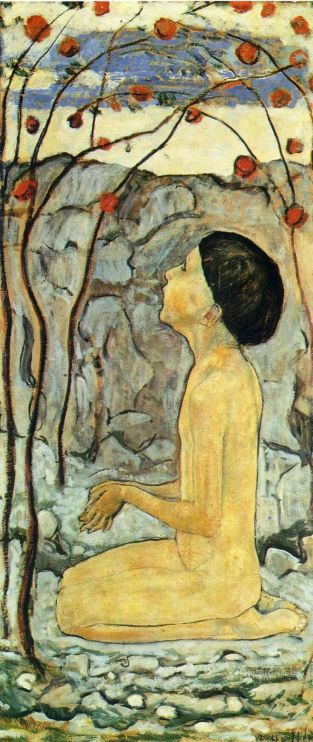

In this picture by Rubin, the day is dawning, with signifies an expression of hope on the threshold of a new era. As discussed previously, the work and style of Ferdinand Holder profoundly influenced Rubin’s work. The image of the young child in a symbolic sense is an image of regeneration. This image of the young child has been used in two of Holder’s paintings, namely, Adoration (1893), and The Consecrated One (1893-1894).

Adoration

The Consecrated One

A clear link to Madonna and Child is evident in Holder’s work and Rubin’s portrayal of the Madonna. In the painting Day (1899), Holder painted five nude female figures seated on the ground in a semi-circle, warmed by the pale light that welcomes the new day, with the central figure with upraised hands.

Ferdinand Holder

Ferdinand Holder

This issue of a nude female with raised hands in the picture the Orant (a representation of a female figure, with outstretched arms and palms up in a gesture of prayer, is an image in ancient and early Christian art). This image of the woman with upraised hands is also seen in Holder’s picture, Truth II (1903). The hands of Rubin’s Madonna are seen in a similar pose. But Rubin’s Madonna, the woman she holds flowers as a sign of the future suffering of the new-born Messiah (p 112, Behold).

We are reminded of Simeon’s prayer the Nunc Dimittis [from the opening words (Vulgate Latin Bible ): now let depart] :

Luke 2:29-12:42 (NRSV)

“Master, now you are dismissing your servant (now let depart) in peace, according to your word; for my eyes have seen your salvation, which you have prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel.” And the child’s father and mother were amazed at what was being said about him. Then Simeon blessed them and said to his mother Mary, “This child is destined for the falling and the rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed–and a sword will pierce your own soul too.”

The words, “…and a sword will pierce your own soul too.” anticipated the fact that the infant Jesus was destined to suffer and die and this would affect Mary profoundly.

Purvis de Chavannes’ masterpiece, The Poor Fisherman (1881), that was exhibited at the Louvre while Rubin was in Paris, France. There is also a connection between this painting and Rubin’s Madonna and the Vagabonds. The image of an infant on the ground and a fishing boat are significant as they recall the words of Jesus to the Apostles Peter and Andrew as they were casting their nets, “Come ye after me, and I will make you to become fishers of men” (Mark 1.17).

Purvis de Chavannes’ masterpiece, The Poor Fisherman

Purvis de Chavannes’ masterpiece, The Poor Fisherman

In the background of Rubin’s of the painting the Sea of Galilee can be seen, is the setting of The Madonna of the Vagabonds, and many other scriptural scenes take place.

The Sea of Galilee is also the place where Jesus walked on the water and he is the fisher of souls. The three empty boats in the water, belonging to the fishermen asleep on the shore viewed in this picture. Are they waiting to be summoned by the Redeemer that has been born? (p 112, Behold).

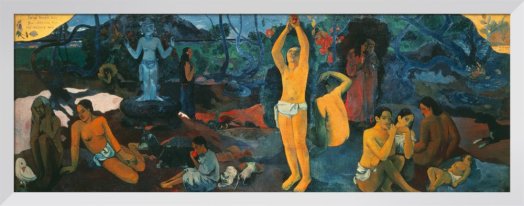

Rubin’s early works that he did in the Land of Israel, have been compared to Gauguin’s portrayals of Tahiti, both wishing to visually portray that which is primodal and pure. It is very likely that Rubin had seen ‘s work on show in New York, USA, while he was there. The figure of Mary has been regarded as the second ‘Eve’, an untainted and noble savage like the women of Tahiti, who were untainted in contrast to the women of Europe who were considered to be decadent and seductive. This was the type of figure shown in the Madonna of the Vagabonds.

Unlike many portrayals of Madonna and Child the woman is not engaged in adoring the baby, but represents a figure with bared breast as a symbol of fertility, with her being seated conveying the message of simplicity and rootedness, rather than a traditional Christian portrayal of her seated on a throne attended by heavenly beings as in Jean Fourquet’s Madonna Surrounded by Cherubim and Seraphim (1452).

The men asleep behind her, the vagabonds are pioneers who have come to build the Land. However, having said that it is still imbued with Christian symbolism. This is not about suffering and death, but hope and renewal, though this is not without pain, hinted by the red flower in the woman’s palm that can just be seen. In it Rubin relates to Jesus in a different guise, as the child will bring redemption and vanquish death, through his resurrection (p 112, Behold).

Some Observations

Though there is a similarity of the composition of the two painting by Rubin, The Madonna of the Vagabonds is diametrically opposed to the Temptation in the Desert.

The tortured figure of Jesus in the Temptation, is replaced by the smiling figure of the Madonna, for she is the antithesis of the Temptation’s femme fatale. The Madonna’s bared breast suggests health and fecundity (the ability to produce young in great numbers), where as the temptress in the Temptation has very different connotations.

“Jesus as a representative of Zionism’s New Jew in the Encounter reappears more powerfully The Madonna of the Vagabonds. The baby Jesus symbolises rebirth in the homeland as well as resurrection after the death of exile” (p 113, Behold). In some ways it can be viewed as a self-portrait of the artist, Rubin, who was about to begin a new life in the Land of Israel.

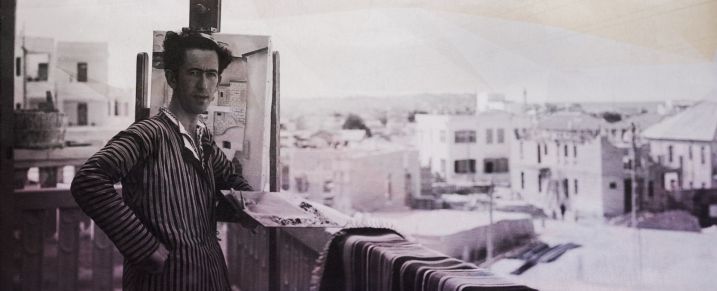

Reuven Rubin in Jerusalem

In April, 1923 Rubin realised his dream of moving to the Land of Israel, and this move brought mixed emotions. Though he was glad to be in the sunshine under clear blue skies, yet he was particularly saddened by the state of art in the country at the time.

He penned these words in his autobiography:

“Now I am in Jerusalem, I tread on the same stones that I first touched eleven years ago, and I roam in the very places where so many God-seekers cried out their anguish and affliction. I came here to spend Tisha Be-Av, the day of sadness over our destruction [the destruction of the Temple], in order to experience it to the full. I should like to stand, quaking, before this immense destruction etched on our backs through the generations, in order to leave here a stronger man, so that I many convince. Whom? Of what? How can I convince? Nonsense, nonsense…

No one has the courage to get up and sweep away all the merchants and pedlars from within the Temple. The Temple must be cleansed! I promise you the day will come when I will pluck up courage and my fist will be strong and my voice reverberate, and then the time will come for me to be the man who will sweep away. But in that case better I should decide to die[?] young. Other wise it won’t work” (p 113, Behold).

Rubin clearly associated himself with Jesus in his cleansing of the Temple, viewing himself as one who had a new message to share, even as a prophet of the Messiah had. His mission was to cleanse the temple of the art world from all that was rotten and old. One the one hand he is excited and enthusiastic by a sense of the spirit of renewal, but on the other hand he feels deeply frustrated and troubled. With this in mind it is easy to understand why he identified with the prophets and Jesus.

Rubin’s Self-Portrait with a Flower

In the painting of Rubin’s Self-Portrait with a Flower, he is wearing the white shirt of a chalutz (pioneer), against a background of sand dunes, tents and houses and a boat is also visible in the corner by the sea. He self-confidently gazes at the viewer out of the corner of his eyes that seem to penetrate one’s eyes. In the one hand he holds a glass with a white flower in it, while in the other, he clutches a number of his artist’s paint brushes.

The most striking feature is the picture is the white lily in the glass, which is a symbol of the Annunciation given to the Virgin Mary concerning the Holy Child that she will bear. Once again this message of renewal in the homeland is stressed. These hands unlike another self-portrait done by Rubin, communicate the importance of the Annunciation to the viewer, and do not bear stigmata as was the case in other paintings (p 113-114).

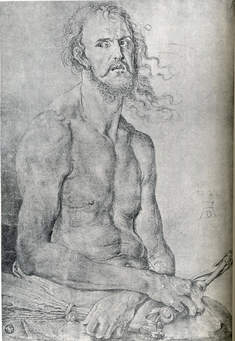

Albert Durer’s – Self-Portrait: Man of Sorrows

In Albert Durer’s – Self-Portrait: Man of Sorrows in both hands he is holding the instruments of torture, a Birch and Scouge (1522), and as Rubin so often spoke and also portrayed himself as a tortured man, there are echos of Durer’s picture. While there is no evidence that Rubin knew of the work, very interesting parallels exist, the unhappy man with a possible accusatory look from the corner of the eyes of both, and in the left hand Durer’s Jesus holds a reed-scepter, while Rubin holds a hand full of paintbrushes.

These two paintings show victims of two different kinds. Durer’s Jesus sacrificing himself for the sake of humanity, while Rubin’s sacrifices himself as a artist-pioneer for the sake of the Jewish nation. The hand holding the paintbrushes may be equated to Rubin’s instruments of torture and suffering and the while the white lily the hope of redemption (p 115, Behold).

Once more in a letter to his friend Bernard Weinberg, Rubin wrote, “Today I passed through the valley [The Jezreel Valley] and this day I saw our crucified of the present time” (p 116, Behold).

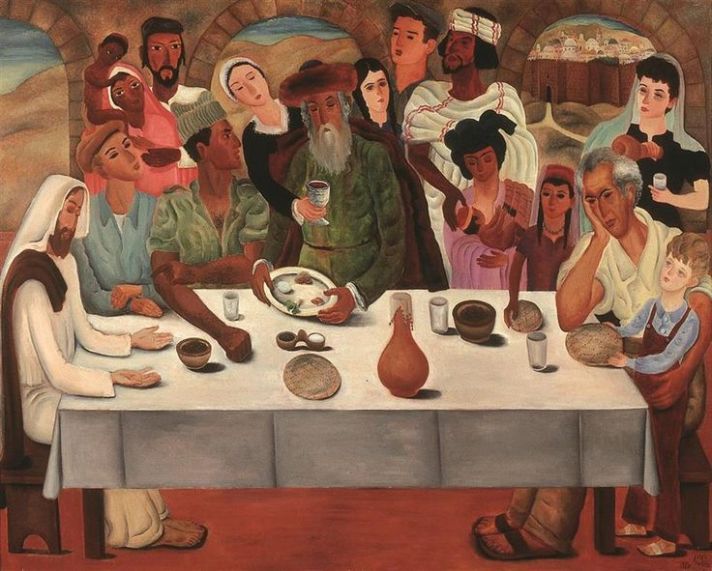

Our final painting that we consider in this programme is Rubin’s First Seder in Jerusalem (1949).

Rubin’s First Seder in Jerusalem (1949).

Rubin’s First Seder in Jerusalem (1949).

Nearly 30 years after Rubin painted, the painting Meal of the Poor and The Madonna of the Vagabonds, and nearly two years after the founding of the State of Israel, Jesus takes his place at the Passover table in Jerusalem. This ritual meal celebrating deliverance and redemption (p 118, Behold)

A Description of the First Seder in Jerusalem

Seated and standing around the table are people from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds, The one thing they all have is common is that they are all in the Land of Israel, no longer British Mandated Palestine, but the new sovereign nation of Israel. These are Jews who have gathered from many nations.

There are Six figures that we should note in particular: a Yemenite looking elderly Jewish man (who could be a rabbi) holding the Passover cup that is raised in one hand and a Seder plate in the other; next to the rabbi is a good looking dark complexioned couple: the man with his wife and she is holding a baby boy (wearing a scull cap) that she is nursing (an echo of a Madonna and Child) and the child’s father is gently touching the babies head, symbolising blessing and also according to Rubi’s imagery, fertitlty; then there is a self-portrait of a seated older grey haired Reuven Rubin with his arm around the shoulder of a young boy who is standing next to him (this could be his son, a native born first generation child born in the Land of Israel who may now be correctly called an Israeli).

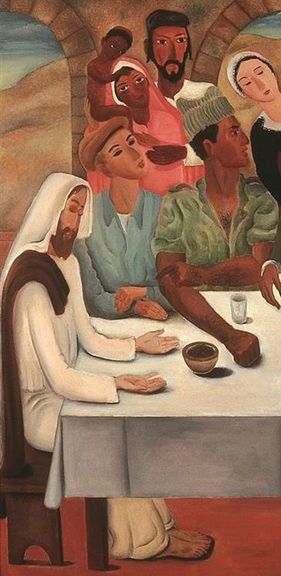

The final figure that I wish to consider is at the other end of the table: Jesus

It is the seated figure of Jesus wearing a white robe, with his open hands bearing the stigmata and placed on the table and with his bowed in prayer. His image in the First Seder in Jerusalem suggests one who is resting in a peaceful state of composure. There are no signs of conflict as viewed in some of Rubin’s other depictions of Jesus, thinking particularly of the Encounter and Jesus and the Last Apostle, in which both portrayals are full of contrition, pain and sorrow. This painting is in some measure the crowning glory of Rubin’s work dealing with the person of Jesus and may be considered a masterpiece!

Traditionally on a Seder night, those living in the Diaspora say: “Next year in Jerusalem,” which is filled with the hope of return to the Land of Israel! But this group at this the First Seder in Jerusalem may proclaim: “This year in Jerusalem,” and I wish to add the words, “Hallelujah!” [Praise the L_rd], because Jesus (Yeshua) is with them too.

Detail of the Figure of Jesus at the First Seder in Jerusalem

Detail of the Figure of Jesus at the First Seder in Jerusalem

“And I will pour out on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem a spirit of grace and pleas for mercy, so that, when they look on me, on him whom they have pierced,* they shall mourn for him, as one mourns for an only child, and weep bitterly over him, as one weeps over a firstborn (Zechariah 12.10 – ESV).

*This relates to the crucifixion of Jesus, and to his being pierced by the Roman soldier’s spear, and this interpretation agrees with the opinion of some ancient Jewish sources, who interpret it as to referring to Messiah the Son of David.

Encounter and Jesus and the Last Apostle

What Kind of Messiah?

There are two doctrines of the Messiah held within the Judaism of Jesus time. In two millennia this view of the Messiah of Judaism has not drastically altered.

Firstly, a political Messiah, and secondly, the suffering spiritual Messiah:

Initially Rubin’s Messiah that he featured in his early paintings was the Suffering Messiah. However, Rubin also held to a Political Messiah who as liberator sets the Jews of the Diaspora free from persecution, suffering and exile. He heals and regenerates them in their return to the Land of Israel.

This reminds us that Jesus is a changed multivalent figure (having various meanings) and links to the revival of the Jewish people in their homeland, in Reuven Rubin’s work (p 118, Behold).

Our final two programmes in this series from Behold the Man: Jesus in Israeli Art is entitled: From Personal Experience to National Identity. This will also be a two part programme (Part A and Part B).